Sedentary Lifestyle and Obesity

If you follow current health trends in the media, you’ve almost certainly heard the now commonly used expression, “Sitting is the new smoking.” In a 2014 Los Angeles Times article, Dr. James Levine of the Mayo Clinic, who is credited with making that statement, also stated: “Sitting is more dangerous than smoking, kills more people than HIV, and is more treacherous than parachuting. We are sitting ourselves to death.”

Though this may sound hyperbolic, the evidence supporting this idea is convincing. When you consider the daily activities of your life, nearly all of them involve sitting – commuting to work or school, your workday, and leisure time. In fact, nearly half of our lives are spent sitting.

Sedentary Lifestyle: A General Overview

Recent history shows us this fact shouldn’t be surprising – it has only been in the last century that we’ve enjoyed the modern conveniences of cars, computers, television, and technology-based entertainment. Fewer and fewer people work jobs requiring regular physical movement, as many of us have moved from the fields and factories into the office. Most urban dwellers travel longer distances between work, home, and places of leisure, and no longer walk or ride a bicycle.

The average person is far more likely to spend an hour per day watching a television program than they are engaging in exercise. In this way, modern life is a blessing and a curse – the price we pay for these luxuries is steep; we may be paying with our lives.

The effects of a sedentary lifestyle are somewhat insidious – creeping up so slowly that one may not recognize their connection to each other, and can include obesity, cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, anxiety and depression, and early death.

According to data from the Center for Disease Control, nationwide, state obesity rates range between 23-39.5% (from lowest to highest), meaning at minimum, 1/4 of the residents of each state are obese. Though many factors come into play regarding obesity, including genetics, medications, lifestyle choices, eating habits and patterns, and socio-economic issues, one of the greatest contributing factors is a sedentary lifestyle.

It takes a conscious decision, dedication, and a little self-discipline, but you can improve the quality of your life and either prevent or reduce the effects of the consequences involved with a sedentary lifestyle. It may mean carefully re-examining how you live your day-to-day life, but the dividends will pay off in increased health, happiness, and, ultimately, a longer life. Here, we will explore what it means to have a sedentary lifestyle, how to fight it, and how to motivate you to become more active.

What Do We Know about the Sedentary Lifestyle?

According to research published by the Korean Journal of Family Medicine in 2017, there are two working definitions of the term sedentary lifestyle: one is defined by the lifestyles and behavior involved, and the other as a lack of participation in minimum levels of activity. It can include seated, desk-based work, increased time in a car or public transportation, and excess media consumption, including watching television, playing video games, and tablet/smartphone use while seated or lying down.

Regardless of how it is defined, both definitions arrive at a similar conclusion – the most important lifestyle change to make is to engage in regular physical activity. Sedentary lifestyles, despite being among the most common ones in the United States, are also a global health concern.

According to recent research conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 23% of adults (reaching as high as 80% in some subgroups) and 81% of adolescents (11-17 years) do not spend enough time dedicated to physical activities, as recommended by their standards.

It is easy to understand why so many of us around the world find engaging in increased physical activity difficult. In many developing countries, particularly in urban areas, rapid expansion provides limited planning or space for parks, sports, and recreation facilities. Additional concerns, including overpopulation, poverty, crime, traffic, and air quality, often inhibit people from wanting to leave their homes to exercise outside.

Still, others include the expense of joining a gym or recreational exercise league, insecurity about personal appearance, and cultural norms around exercise. That is not limited to urban areas – rural areas of developed and developing countries are now showing increasing trends of sedentary lifestyle habits, particularly in rest after the workday. Though all of these arguments are valid, the fact remains that a sedentary lifestyle is unhealthy, unsafe, and under-recognized for the pandemic that it is.

Obesity and the Sedentary Lifestyle

A sedentary lifestyle goes hand in hand with obesity. The WHO has determined that it is the second-highest contributing factor to obesity, the first being an intake in energy-dense foods. That is not limited to caloric excess; however, an unbalanced and unhealthy diet and malnutrition or undernutrition from only having poor quality food available are also problems for many, especially for low-income families. There is also a strong correlation between sedentary behavior and other unhealthy behavioral patterns like binge eating and “boredom eating.”

Though this is not true for everyone, almost all of us can shamefully admit to too many slices of pizza or a pint of ice cream while watching our favorite show on a Friday night. Recognizing our patterns and excuses for being sedentary is easy. Once we examine them, making changes, however, is much more challenging.

Sedentary Lifestyle Statistics

A 2019 report published in Ergonomic Trends provided interesting statistics regarding the sedentary lifestyle, its trends, and its effects, including the following:

- A sedentary lifestyle increases mortality rates by 71%

- Physical activities will not minimize all negative effects of sitting behavior – sitting for 5-6 hours per day, despite a regular exercise regimen, will result in a 50% increase in mortality rates.

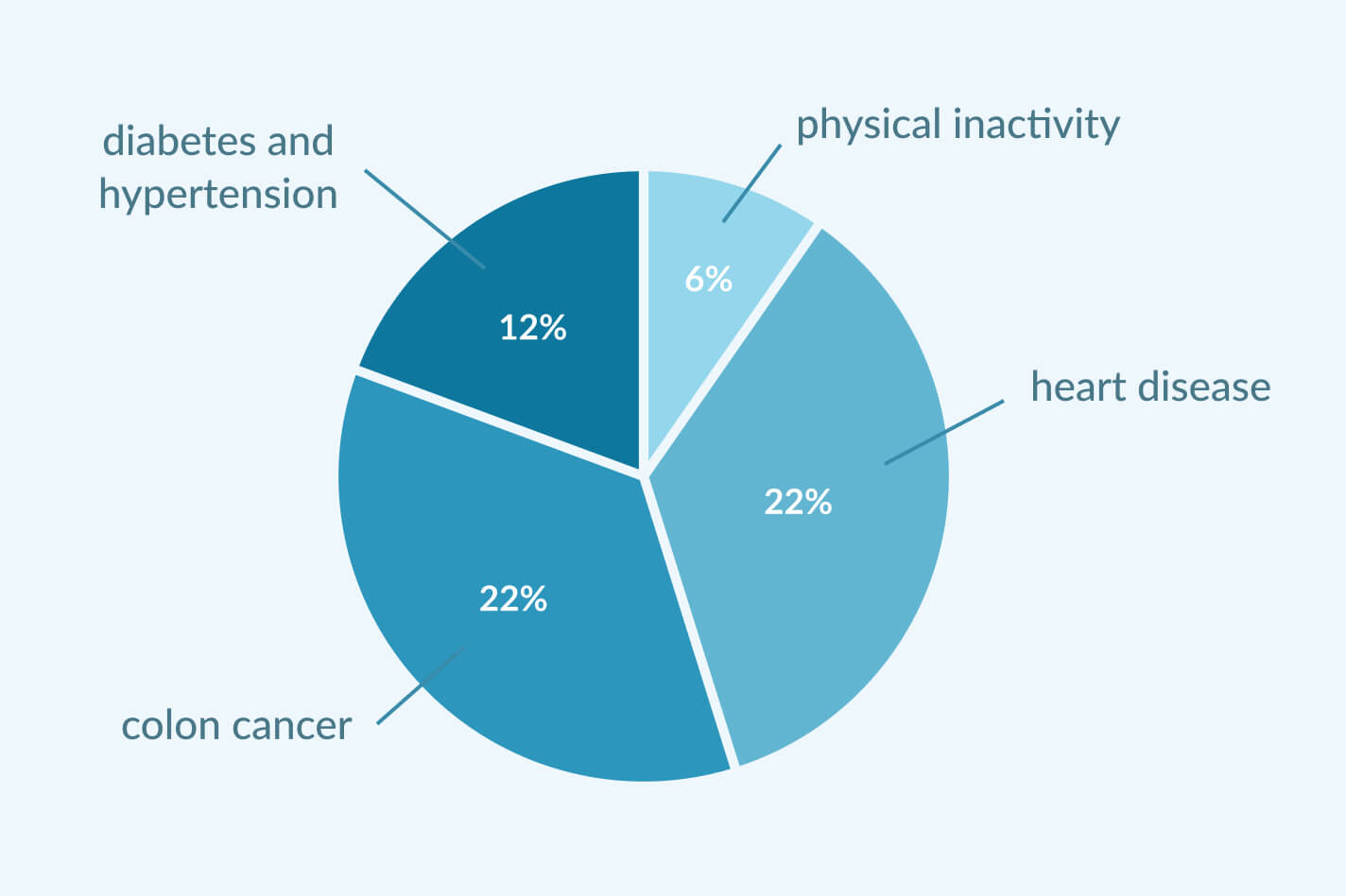

- A sedentary lifestyle is the 4th leading risk factor for global mortality. Approximately 6% of global mortality rates are associated with physical inactivity, including:

- 22% from heart disease

- 22% from colon cancer

- 12% from type 2 diabetes and hypertension.

- A sedentary lifestyle is reported to be linked to a 112% risk of developing type 2 diabetes, and a 147% increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

- Women are more prone to maintain a sedentary lifestyle in comparison to men, which may be attributed to the nature of their work, which is often desk-bound or seated.

- According to a UN report, in 159 of 168 countries, women were 10% more likely to be physically inactive; in 9 countries, 20% or higher.

Though these statistics are shocking, not all of them had negative connotations. Some, in fact, maybe the encouragement you need to consider increasing your physical activity levels and include the following:

- Reducing the length of time you sit may lower your risk of death by 55%.

- A study conducted by Columbia University indicated sitting in 30-minute stretches was the most effective way to accomplish this goal.

- Moving two minutes per hour may reduce your risk of premature death by 33%.

Health Implications of a Sedentary Lifestyle

Without a doubt, a sedentary or inactive lifestyle has many, far more serious outcomes than simple adiposity or obesity. In his paper, “Sick of Sitting,” Dr. James Levine notes a phenomenon called “sitting sickness,” citing a jaw-dropping 35 chronic diseases and conditions associated with a sedentary lifestyle, which affect approximately 70% of patients in the United States.

It has larger implications than for the patient alone – the chronic diseases and conditions involved are a massive healthcare cost burden. They will likely continue to rise as the rates of complications from sedentary lifestyles do. The most commonly occurring diseases and conditions associated include:

- Hypertension

- Osteoporosis

- Neck, back, and sciatica pain

- Cognitive dysfunction in older adults

- Metabolic syndrome

- High cholesterol

- High blood pressure

- Increased risk of stroke

- Lung, breast, colon, ovarian, endometrial and prostate cancers

- Cardiovascular disease

- Deep vein thrombosis

- Depression and anxiety

- Type 2 diabetes

- Erectile dysfunction

- Increased risk of addiction to alcohol, tobacco, and opiates for chronic pain management.

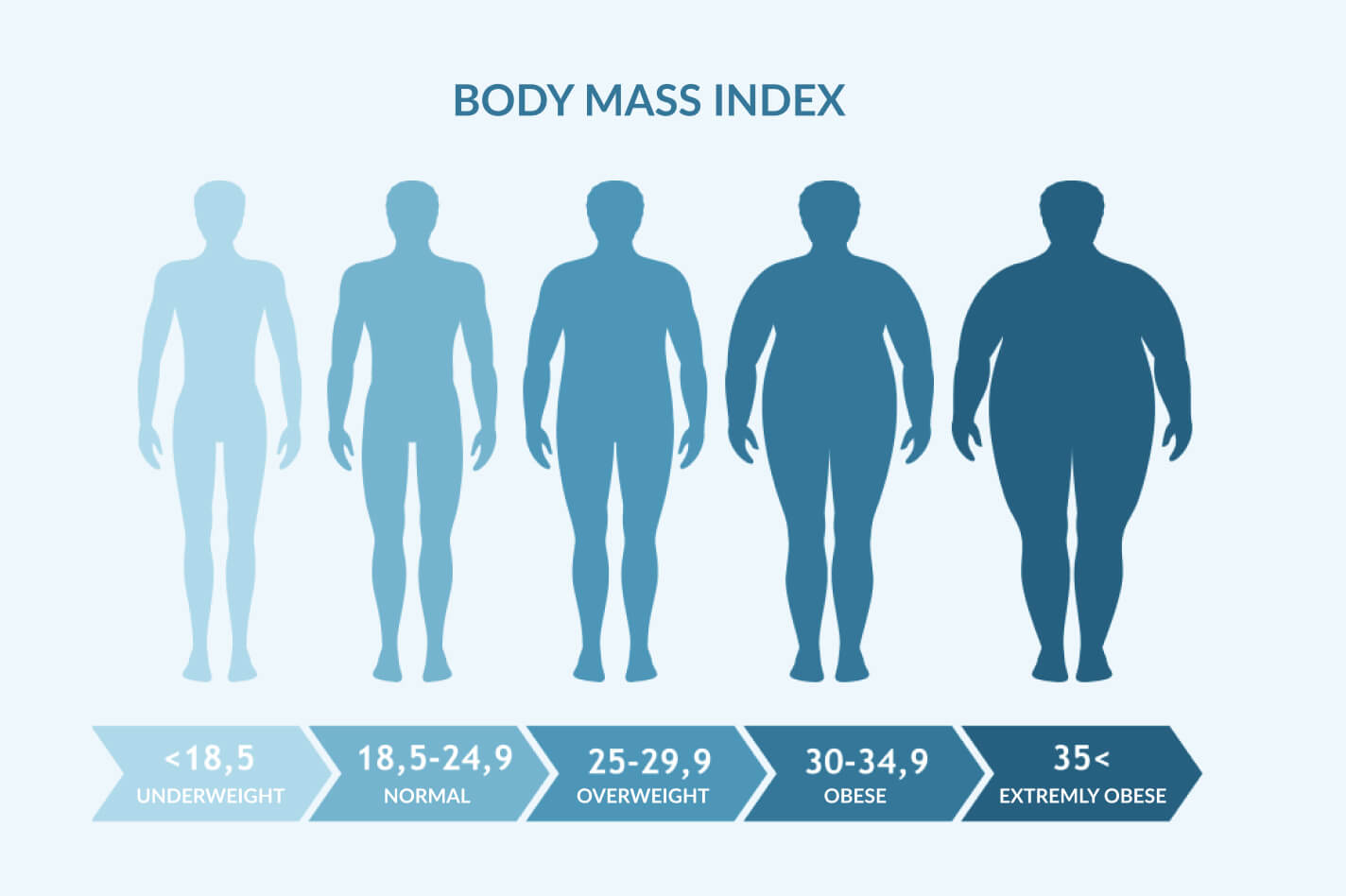

Though it may be tempting to assume obesity is a direct result of sedentary behavior and obesity, the fact remains that there is not sufficient evidence to make that claim. A 2017 review by Stewart Biddle on sedentary behavior and obesity risks in adults emphasizes that besides an inactive lifestyle, other determinants may be in play. For instance, in some cases, higher obesity and increased body mass index (BMI) was directly linked to sedentary behavior in childhood and adolescence.

On the other hand, lower BMI was associated with the frequency of breaks in sedentary time. Therefore, it is possible to conclude that a sedentary lifestyle does not exclusively cause obesity per se, but recognition of its involved risks should be strongly considered, and behavior patterns should be closely examined.

If you believe you are experiencing symptoms or effects like those mentioned above, particularly with regard to mental health concerns, we highly recommend seeking professional help, especially if they are interfering with your everyday life and overall well-being. Your health care provider can be your partner in developing a plan to safely increase your activity levels, assess your nutrition, and address your physical and emotional needs.

They may also be a valuable resource for access to healthier food options and provide support for encouraging physicality. Many physicians, for example, may now prescribe gym activity, and provide their patients with discounted or free gym memberships or exercise classes.

How to Reduce the Sedentary Lifestyle Impact on Your Health?

We all know the well-used turn of phrase, “Rome wasn’t built in a day.” Similarly, the process of becoming more physically active will take time. Your health care providers understand that making a drastic lifestyle change is sometimes impossible due to various reasons beyond one’s control.

Making small adjustments, however, may not only feel less intimidating but may also help you seek out other ways to move your body with more regularity. Examples include taking evening walks or a run, using stairs and not elevators when possible, parking further away from the door when shopping, and stretching during commercial breaks.

You’ll be surprised how many benefits there are, including increased flexibility, pain reduction, improved circulation, and improved breathing. Beginning to break the cycle of a sedentary lifestyle can begin by simply standing up!

It’s important to remember that the process of increasing your activity levels has as many mental benefits as it does physical ones. Research, as recent as 2008, suggests that engaging in regular physical activity can reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression because the brain produces chemicals called endorphins.

When released, they provide the body with a feeling of happiness, similar to that of taking a pain reliever like morphine. Have you ever heard of the expression “runner’s high?” That comes from the feeling that occurs, releasing endorphins into your system after a strenuous exercise session – you’ll find you feel so good, you crave it as you become more active!

Before beginning a regular exercise regimen, however, it is good practice to consult with your healthcare provider to ensure you are doing so safely and appropriately.

How Can We Fight Sedentary Lifestyles in the United States?

The battle against sedentary lifestyles has many allies, chief among them are The Center for Disease Control and the National Institute of Health. Together, they have developed a national agenda called Healthy People 2020 to target the greatest areas of public health concern, develop preventative models to address them, set nationwide goals to reduce their risk and to promote healthy lifestyle choices.

It currently addresses 42 areas, including nutrition and weight status, physical activity, and social determinants of health, each of which has a direct effect on sedentary lifestyles and nutrition. Here, they provide an overview of current national trends, objectives of government programming for health promotion and prevention of disease, interventional plans, and educational resources.

Examples of their efforts can be seen here:

| Topic | Examples of Objectives | Examples of Interventions |

| Nutrition and weight status |

Access to healthier foods

Increasing the number of physician office visits including counseling or treatment related to nutrition and weight Encouraging worksites to offer nutrition management classes or counseling Reduce the proportion of obese adults and increase the proportion of healthy weighted adults Eliminate food insecurity Encourage the incorporation of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains into the American diet, especially for children |

Implementation of telehealth visits for patients with chronic health conditions (e.g., diabetes) to discuss dietary interventions

Interventions with schools to increase the availability of healthier meals and snacks in schools Development of clinical guidelines on the evaluation and treatment of overweight and obese adults |

| Physical activity |

Reduce the proportion of adults that engage in no leisure time activities

Increase number of adults who meet current federal activity guidelines Increase the number of adults who engage in moderately intense activity for 150 minutes/week Increase the number of public and private schools that require physical education for all students |

Development of community-wide campaigns to encourage physical activity

Development of individually adapted health behavior change programs Development of health and safety standards for early childcare and education programs |

| Social determinants of health |

Increase the proportion of people with health insurance

Increase the number of people with a regular primary care provider Increase the proportion of persons who report their health care provider always gave them easy-to-understand instructions about what to do to take care of their illness or health condition |

Development of national urban design policies around physical activity and obesity through the CDC

Development of evidence-based practices around communicating the social determinants of health to the public Development of state-by-state health equity initiatives to address inequalities in healthcare |

How Much Should I Move to Reduce Risks?

The most important factor to consider when beginning a new exercise regimen is consistency. The American College of Cardiology recommends that beginners exercise for short periods of time multiple times per day (e.g., 5-10 minutes/day, 3 times/day), as much as they can safely tolerate, and gradually work their way up to longer periods of time and higher frequencies. Selecting activities you enjoy is essential to keep it from feeling “like a chore.” Developing structure, and incorporating exercise into your daily schedule will become easier as you make it a regular part of your life.

Simply moving your body, however, is not enough. As you dedicate yourself to engaging in more physical activity, increasing the intensity will improve your results. To make this easier, the US Department of Health and Human Services has developed specific recommendations, the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, which recommends adults perform a minimum of 150 minutes of moderately intense physical activity two or more days per week and muscle-strengthening exercises two or more days per week.

A sedentary person should engage in activity that increases their heart rate at least 20-30 beats above their resting heart rate to begin. As they work their way up to moderate intensity, their target heart rate (THR) should be 50-70% of their maximum heart rate. To calculate this rate: subtract your age from 220, and your THR will be 50-70% of that. For example, a 42-year-old woman would have the following THR: 220 (maximum heart rate) – 42 (age in years) = 178. 70% of 178 would be 124.

So, she would want to do an activity that gets her heart rate up to 124 beats per minute for a moderate-intensity workout. Examples of moderate-intensity would include brisk walking, dancing, biking, or swimming.

How Do We Motivate People to Be More Active?

Perhaps one of the most important ways to motivate yourself to be more physically active is to start with how you think about exercise – ask yourself if there is a reason why you don’t engage currently, and if that reason is valid.

Look at your past behaviors and compare them to your present ones – what’s different? If there is a difference, what may be the cause? Finally, are these causes something you can change?

We’d like to offer some points to keep in mind while as you begin your journey to a move active lifestyle:

Remember, a healthy lifestyle will not happen overnight

Fitness, like anything, is a learning process. There is a learning curve to becoming fit, including knowing your limitations, understanding the benefit of certain types of movement (e.g., aerobic exercise vs. weight lifting), and how to use exercise equipment safely and correctly. You can’t expect to run a marathon on your first day on the treadmill. You can’t expect to deadlift a 100-lb weight on your first try. Don’t let this be discouraging; let it be a goal you will eventually reach. Go at your own pace.

Keep your exercise regimen shame-free

If you’re at the gym and feel unfamiliar with a piece of equipment, don’t be afraid to ask a staff member for help – that’s why they are there!

If you miss a day of working out, don’t place a judgment value on it – you haven’t done anything wrong. It is easy to become discouraged and want to give up entirely when you feel like you’ve failed. Simply pick up where you left off.

Are you feeling insecure about your body? We all do. It’s a very common source of anxiety. It should not limit you, however, from reaching your fitness goals. Select athletic wear that you feel comfortable moving in, and take pride in the fact that you are working to make a change in the way you look and feel!

Develop a plan you know you will commit to

Be honest with yourself about what you have the time, means, and willingness to do. By staying within those boundaries, you are less likely to make excuses and more likely to get to work!

Make it a family affair! Everything’s better with a friend!

Sometimes, taking the first step is easier with support. Ask a friend or family member to be your workout partner. Having someone hold you accountable and cheer you on in your efforts can keep you focused and engaged.

Give yourself a tangible goal

A “prize best motivates some people.” Do you have a piece of clothing you’d like to fit into? Perhaps a trip somewhere? Keep your prize in mind as you work out, and remember what you’re working towards when you’re feeling challenged.

Ask for help

Do you know someone who motivates or inspires you? Ask them how about their process. You may find tools available you weren’t aware of before!

It’s all about you!

This is your health and your body. Don’t let someone else’s expectations push you outside of your comfort zone or make you feel ashamed.

Keep a food journal for a month

Look at everything you eat, including portions, time of day, and snacks – are your calories in greater than those going out? If so, adjust your fitness plan accordingly to ensure you’re burning them off to prevent weight gain.

Consider challenging yourself with something you have difficulty doing (e.g., .climbing stairs, hiking)

There is an iconic scene in the movie Rocky where he practices running up and down the stairs of the library in Philadelphia until he is finally able to do it without stopping. Practice your challenge regularly until it’s no longer difficult.

Celebrate your victories!

Don’t be afraid to share your success with the people closest to you! Taking pride in your accomplishments will likely help you push beyond what you thought possible, develop further goals, and keep you on the right path when you’re tempted to wander off.

Bottom Line

Our intent here is not to alarm or disturb our readers, but rather call you to action. Obesity can be controlled and prevented. Your physical health can be improved, as can your overall quality of life. A positive first step in that direction is incorporating regular physical activity into your daily life. Change can be hard.

It can be scary. It can also be empowering. We wish all of our readers luck and success in their fitness goals, encourage you to consult your physician before beginning a rigorous regimen, and, most importantly, to have fun!

- Macvean, M. (2014, July 31). “Get up!” Or lose hours of your life every day, scientist says. Los Angeles Times.

https://www.latimes.com/science/sciencenow/la-sci-sn-get-up-20140731-story.html - State of Childhood Obesity.org. (2019). Adult Obesity Rates. Retrieved from

https://stateofchildhoodobesity.org/adult-obesity/ - Gonzalez, K., Fuentes, J., Marquez, JL. (2017). Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, and Chronic Diseases. Korean Journal of Family Medicine. Retrieved from

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5451443/ - World Health Organization. (2020). Physical inactivity: a global health problem. Retrieved from

https://www.who.int/ncds/prevention/physical-activity/inactivity-global-health-problem/en/ - Levine, J. (2015). Sick of Sitting. Diabetologia. Retrieved from

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4519030/ - Mueller, J. (2019). Sedentary lifestyle: the shocking statistics that will get you off of your chair. Retrieved from

http://ergonomictrends.com/sedentary-lifestyle-sitting-statistics/ - Biddle, SJH., Garcia Bengochea, E., Pedisic, Z., Bennie, J., Vergeer, I., Wiesner, G. (2017). Screen Time, Other Sedentary Behaviors, and Obesity Risk in Adults: A Review of Reviews. Retrieved from

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28421472 - Ali, YS. (2020). How to Fix a Sedentary Lifestyle. Retrieved from

https://www.verywellhealth.com/how-to-beat-a-sedentary-lifestyle-2509611 - Berry, J. (2018). Endorphins: Effects and how to increase levels. Medical News Today. Retrieved from

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/320839 - Traynor, K. (2016). Planning an Exercise Regimen for the Sedentary Patient: What a Cardiologist Needs to Know. Retrieved from

https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2016/05/16/08/23/planning-an-exercise-regimen-for-the-sedentary-patient - ODPHP, (2015-2020). Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Retrieved from

https://health.gov/our-work/food-nutrition/2015-2020-dietary-guidelines/guidelines/appendix-1/

Comments